As social networking and particularly collaboration technologies have flourished, so have a whole new crop of terms intended to describe what differentiates these new capabilities from the old. One of the new terms is “shared workspace”. It’s now common for vendors to tout their new “workspace” somewhere in their marketing. But beyond the claims, there is little discussion about what is really meant by the term. My intention is to dig a little deeper into describing what most current vendors mean by a “shared workspace” and the characteristics that distinguish a next-generation workspace.

Knowledge workers of today who are more often remote and mobile do certainly benefit from technologies that provide the virtual equivalent of the old whiteboard in a meeting. Not surprisingly, there is a wide spectrum of capabilities that various vendors use to describe their “workspace”. The single common understanding is that “shared workspaces” support collaborative input, editing, and updates from more than one person at the same time, i.e. it’s a multi-user tool. While email technically allows any party in the dialog to add a comment at any time, the general idea is more like ping-pong. One person sends a note and another person responds. The first person waits for the response; it’s a back and forth paradigm. Email certainly presented a new “workspace” to users 30 years ago. Current day tools support capture of anyone-anytime-anywhere dialog in the context of a work group or project.

Some consider a shared document to be a workspace. Enabling multiple people to view and edit the same document at the same time is certainly a huge step beyond email, but producing shared documents is only a relatively small part of what knowledge workers do.

Modern workspaces also provide the basic capabilities of storing and retrieving shared documents in a shared repository. A shared workspace typically also includes ready access to your colleagues organized by group or project and the ability to post comments in a shared view.

The software provided by most of today’s vendors utilize a one-to-many paradigm. The workspace is a shared forum in which collaborators update each other in real time. Anyone in the group can post updates at any time, and all group members are updated simultaneously. While keeping colleagues up to date is important, such workspaces engender intermittent participation from team mates and the workspace provides only limited focus on individual accountability for who is delivering what by when.

The most advanced workspaces, however, go much further. The software is not just an open field where participants have the possibility to add a comment or respond to someone else’s post. The workspace technology actually functions like a facilitating third-party to the conversation.

I take it for granted that the workspace must be easy to use. Who doesn’t make this claim? A more interesting differentiating characteristic is whether the workspace is passive or active.

Passive vs. Active workspaces

Passive workspaces sit there, a virtual blank canvas that collaborators can write on together. The passive workspace collects and displays the inputs from participants and may even provide some search (e.g. tags) and sorting features, but the technology offers nothing to directly influence the content, style, or mood of the communications that are going on.

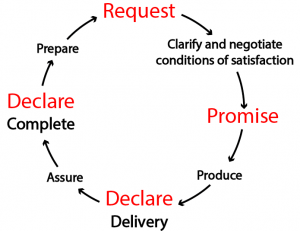

Active workspaces act like a third party in the work conversations. An active workspace guides the participants into how to conduct a focused collaborative action that leads to results. It facilitates a certain structure and rigor, the rules of engagement so to speak. The conversation is “managed” so as to increase the likelihood of a successful delivery. The software is also specifically designed to facilitate the quality of the conversation (e.g. who says what to whom) and in so doing to build a positive relationship between the parties going forward. Task and relationship management are combined.

Eight characteristics of a next-generation workspace

Following are 8 specific characteristics of active, next-generation workspaces that are not yet generally available in the marketplace:

1– Context. Entries are organized in a thread that is specifically related to some action or result someone has requested, i.e. not just a general posting.

2– Focus. Dialog is focused on what we are trying to accomplish, i.e. the explicit requested outcome by when. Who is involved, who is the accountable performer, and who else is an interested observer to the conversation? What’s the current status, i.e. is the task on track or not?

3– Structure. Composing the goal or task request must contain certain information. Structure cannot be so confining, however, as to inhibit the flexibility needed for natural conversations.

4– Ownership. Views show who’s got the ball at this moment to move the conversation along. Who is waiting for who?

5– Next steps. What are the appropriate next actions any user could/should take next? The software provides a set of shared ground-rules for “managing” the conversation including expected responses at any particular point in the dialog. An underlying “intelligent” workflow keeps things moving forward.

6– Setting the mood. The software prompts what “words” are appropriate to set up the optimum “mood” for the conversation that will enhance respect, engagement, and trust.

7– Closing the loop. Delivery of agreed outcomes is explicit. Performers don’t claim “done”; instead they assert that a delivery was made and let the original requester confirm whether the delivery was satisfactory. Team leaders accept and express satisfaction and feedback.

8– A history. Memory of past conversations is preserved for later review and analysis. Participants build their reputation as a reliable team member. One’s integrity (i.e. say what you’ll do, do what you say) is catalogued and supported by data. Trust improves.

4Spires solutions are examples of next-generation workspaces that include all of these characteristics.